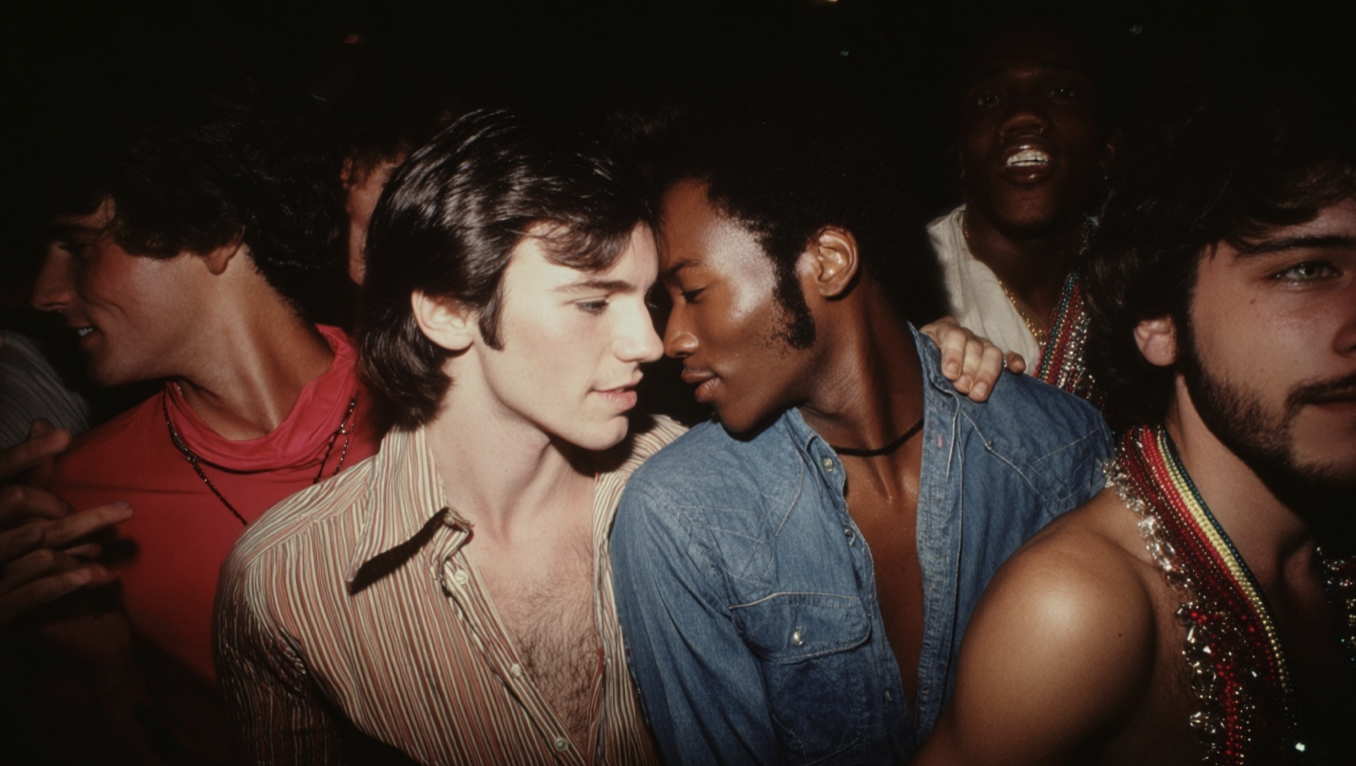

Dazzling beams, glittering mirror balls, and the pulsating rhythms of disco music conjure an atmosphere of fervent celebration and transcendence, one meticulously embodied by the icon Sylvester, sometimes hailed as the Queen of Disco. His 1978 anthem You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) is not merely an exuberant dance track but a profound spiritual statement set against the socio-political turbulence of late-20th-century America. In the wake of the Vietnam War, the Stonewall Riots, and the assassinations of prominent civil rights leaders, disco emerged as a sanctuary for marginalized communities, especially Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ youth, offering a vibrant counter-narrative of joy, identity, and communal belonging.

Sylvester’s performance of You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) is strikingly liturgical, combining gospel-infused vocals with the sonic depth and transcendental energy of disco. The song’s origins as a mid-tempo R&B ballad transformed by the production genius of Patrick Cowley into an enduring disco anthem underscores its cultural and musical significance. It not only dominated dance floors but became a rallying cry for queer self-expression and liberation, resonating deeply within LGBTQ+ communities. Recognised by the Library of Congress, which preserved the track in the National Recording Registry in 2019 as a culturally significant work, it stands alongside selections of music considered pivotal in America's auditory heritage.

Yet, disco's rise was met with fierce opposition from religious groups. Publications within Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh-day Adventist circles condemned the music as a perilous indulgence of carnal desires, associating it with moral and social decay. Some Adventist critiques went so far as to link disco to the symbolic signs of an impending apocalypse, framing it as a disconcerting distraction, a stark contrast to the genre's embrace by its creators and followers as a medium of spiritual and bodily freedom. This dissonance reflects a broader historical tension within Christian traditions, especially those influenced by Platonic thought, which often suspiciously regarded the body and sensory pleasure.

The spiritual dimensions of disco, as revealed through its ceaseless rhythmic pulse and ecstatic immersion, challenged these notions. Scholar Iain Chambers eloquently described disco as an 'ever-present now,' a continual explosion of musical presence that dissolves conventional temporal and physical boundaries. This experience echoes classical concepts of transcendence, where the self momentarily surpasses its "skin-enclosed" limits, an essence Sylvester and his contemporaries harnessed through the fusion of gospel fervour and dancefloor euphoria.

These dancefloors became alternative sanctuaries, a form of vernacular devotion where the excluded could centre themselves physically and spiritually, celebrating survival and identity through movement and communal joy. Disco's repetitive beats and syncopated basslines can be seen as kinetic liturgies, illuminating theological reflections previously constrained by traditional modes of worship. The raw, honest expression of joy through body, mind, and spirit offers a holistic approach to spirituality that many orthodox institutions have historically resisted.

For many gay men, especially those facing rejection from religious institutions, disco symbolised a vital space of affirmation. Sylvester himself, who began his career as a gospel singer before being marginalized due to his identity, transformed his music into an embodied act of resistance and freedom. His songs exhorted listeners to find liberation and authenticity in their bodies and relationships, a radical theological act in its own right.

The author’s reflection on personal experience, though not a dancer himself, signals a broader cultural moment: the recognition that sacredness resides not only in solemn hymnody but also within the saturated, ecstatic spaces of disco. This reimagining of worship challenges the often restrictive boundaries imposed by religious orthodoxy and underscores the urgency for inclusive spiritual expressions, particularly amid ongoing violence and systemic marginalization of LGBTQ+ people. The recent doubling of anti-LGBTQ+ bills in the US and disheartening institutional statements deepen the urgency for new liturgies of resistance and belonging.

Within this context, disco’s shimmering, ecstatic spirit is not merely nostalgic; it is a vital cultural and spiritual resource. It invites us to reconsider the theological potential of embodied joy, communal liberation, and the dissolution of boundaries between the sacred and the secular. Just as Yale Professor Linn Tonstad observes, dancing is at once a celebration of life’s ephemeral beauty and a humble acknowledgment of mortality, 'grass that wilts, withers, and dies', yet in its kinetic joy, we find a language for the liberation we seek both now and beyond. Source: Noah Wire Services